In his 2008 book

Strange Fruit: Why Both Sides Are Wrong In The Race Debate Kenan Malik makes what I consider to be a strange point. Taking a lead from historian Jonathan Israel, Malik distinguishes two strands of the Enlightenment: a mainstream strand and a radical one. Why should he do this?

Prior to reading Strange Fruit the only distinction I had made within the rich thought of that period in human history was between anyone who even loosely associated themselves with the project of human progress (with its attendant themes of education, science, deism and atheism, liberty, equality, etc), and those conservatives (De Maistre, Burke et al) who were firmly against it. Of course there were certainly differences between the Enlightenment thinkers (for the period was extended in time and place) but to introduce a more formal division between these thinkers as a key to understanding them is, I think, a bad move.

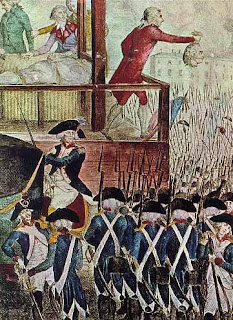

I can see the appeal of the division. A great many Enlightenment thinkers - especially those in France for obvious reasons - developed the ideas that had begun with the religious scepticism of Descartes in the early 17th century and took these to their logical political conclusions: atheism, absolute equality, and eventually revolution. In more recent times the extremist nature of this philosophy has been dismissed as 'reason gone mad', and so it is a worthwhile task to reclaim such ideas as being entirely appropriate to the conditions of the time, and perhaps to outline the conditions of their becoming appropriate again.

So there is a case for favouring the radicals as Malik does here:

The mainstream Enlightenment of Kant, Locke, Voltaire and Hume is the one that we know and that provides its public face. But the heart and soul of the Enlightenment came from the radicals, lesser-known figures such as d'Holbach, Diderot and Condorcet.

(Strange Fruit, Oneworld Publications, 2008, page 88)

Now, I've nothing against celebrating these "lesser-known" thinkers, but the danger is this: in aligning ourselves with them, and against the thinkers of the so-called mainstream Enlightenment, we potentially cut ourselves off from an even more radical philosophy: dialectical materialism. Much as I admire and agree with the remark attributed to Diderot that "Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest", Rousseau's "Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains" (from The Social Contract) is altogether more shattering, locating the contradictions highlighted by the

philosophes not in religion or the monarchy but in the very structure of society. Malik doesn't say whether he considers Rousseau as belonging to the radicals or the mainstream, or whether he had a foot in both camps, but at the time Rousseau clearly distanced himself from the salons attended by the radicals. He was hardly a man of action; more the solitary walker.

Ditto Kant, whom Malik does label as "mainstream". Admittedly, Kant never left Konigsberg his entire life, and didn't write his famous Critique of Pure Reason until he was nearly 60 years old, but he was an admirer of Rousseau and the philosophy that was born of his transcendental idealism revolutionised the relationship between the subject and the object – after his Critique of Judgement no longer were these to be seen as separate spheres with problematic links but as two intimately related aspects of man's existence.

To dismiss Kant as mainstream – notwithstanding the adoption of much of his philosophy by conservative thinkers in later years – is to deprive oneself of a key to understanding the development of dialectical philosophy and Marxism. There is much more to revolution than the evisceration of priests and the throttling of monarchs.

It is strange that Malik makes this distinction because the argument in Strange Fruit doesn't rely on it. Had he claimed that the Enlightenment

in general was characterised by a commitment to equality and a refusal to see indigenous peoples as 'alien', I'm quite sure that no one would have challenged that point. But by separating out the radicals he is at one point forced to make the rather silly claim that David Hume was a conservative and that he was “forced to acknowledge” the importance of political equality and human unity (page 91), as if the Hume's philosophy would naturally have been that of Burke were it not for the threats of Diderot.

Strange Fruit is an important book for understanding the scientific and political history of the race debate, and for arriving at a view on how racism and anti-racism should be treated today. But that section on the two Enlightenments sticks out like a sore thumb. What we need instead is an argument that links both these strands, bringing together both its radical and dialectical characteristics.

Today's non-launch of NASA's Ares I-X rocket was the closest thing I've had to excitement for a while. I didn't realise that watching a stationary object remain stationary for about 4 hours could be so...tense. It wasn't quite up to the standards set by Ron Howard's Apollo 13, but it easily beat the episode of 'Murder, She Wrote' being broadcast simultaneously on terrestrial TV.

Today's non-launch of NASA's Ares I-X rocket was the closest thing I've had to excitement for a while. I didn't realise that watching a stationary object remain stationary for about 4 hours could be so...tense. It wasn't quite up to the standards set by Ron Howard's Apollo 13, but it easily beat the episode of 'Murder, She Wrote' being broadcast simultaneously on terrestrial TV.